In Loving Memory

April 29, 1947 - September 5, 2020

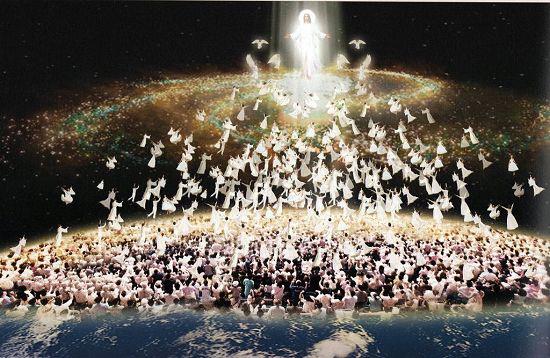

Update: On Saturday, September 5th, 2020, the founder, administrator, and head moderator of this forum, Valerie S., went Home to be with the Lord. Her obituary can be found on https://memorials.demarcofuneralhomes.com/valerie-skrzyniak/4321619/index.php.

1 Thessalonians 4:15-18

For this we say unto you by the word of the Lord, that we which are alive and remain unto the coming of the Lord shall not prevent them which are asleep. For the Lord Himself will descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God: and the dead in Christ shall rise first: Then we which are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air and so shall we ever be with the Lord. Wherefore comfort one another with these words.

2 Timothy 4:7-8

For I am already being poured out as a drink offering, and the time of my departure is at hand. I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. Finally, there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous Judge, will give to me on that Day, and not to me only but also to all who have loved His appearing .

As some of you possibly know, Marjorie Holmes was a bestselling inspirational Christian writer. She wrote nonfiction books such as I've Got to Talk to Somebody, God and at least 3 novels that I know of.

The three novels I know of consisted of a trilogy covering the life of Jesus. They were written and published in this order: Two from Galilee: The Love Story of Mary and Joseph (the word "love" was taken out of later editions, alas), Three from Galilee: The Young Man from Nazareth, and The Messiah.

In this thread, I'm going to post excerpts from all three books, for your enjoyment. If anyone wants to read these novels in their entirety, it should be possible to order copies through Amazon.com.

I'll start in the first reply.

TWO FROM GALILEE: THE STORY OF MARY AND JOSEPH

WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION BY THE AUTHOR

THE MAGNIFICENT BESTSELLER

THE GREATEST LOVE STORY OF ALL TIME

Copyright © 1972 by Marjorie Holmes Mighell

Introduction copyright © 1986 by Marjorie Holmes Mighell

From hardback jacket dust:

One hushed Christmas Eve several years ago a woman sat in a darkened church. The greens, the carols, the beauty of the night—all contributed to the expectant stillness that filled the church. Suddenly she became aware of the strong sweet smell of the hay in the candlelit manger.

“It actually happened,” she thought in wonder. “It happened to real people in a real place with real smells and sounds and sights. And that young mother was no older than my own daughter.”

The impact of the discovery was overwhelming, and the woman left the church that night determined to tell the story of two real people whose lives were touched by God. The woman was Marjorie Holmes, and the story that was born in the scent of the hay was TWO FROM GALILEE.

And what kind of story is it? The author calls it “the greatest love story of all time—told for the first time as a love story.” Never before has there been a major novel about the love between the two people chosen by God to provide an earthly home for His Son. Never before has an author attempted to reveal the human aspect of the Holy Family without departing from a Scriptural base.

The purpose of this novel, in the author’s words, is to “breathe some life” into the participants of this great drama. “If the Bible story is not just a pretty myth but a reality, then they did live and dream and long and hope and suffer,” she says. For this reason, she has carefully unfolded the story of a young love that matures and deepens as Mary and Joseph face the difficulties created by the unexpected announcement that she is with child. As they come to know one another they are joined together by their love of God, their eagerness to do His will, and their mutual responsibility to the Child Mary carries.

This is a novel for young and old alike—for lovers, for mothers, for everyone who finds the Christmas story a source of timeless beauty and wonder. It is a story of divine love much needed in times like ours.

From back cover of 1986 paperback edition:

Here from Marjorie Holmes, one of the most beloved authors of our day, is the extraordinary bestselling novel that tells the story of Mary and Joseph as it has never been told before—the greatest love story of all—

TWO FROM GALILEE: THE STORY OF MARY AND JOSEPH

This is the story of two real people whose lives were touched by God: two people chosen by God to provide an earthly home for His Son. Here are Mary and Joseph—a teenage girl and a young carpenter—alone, frightened, in love, faced with family conflict, a hostile world, and an awesome responsibility. It is a story for young and old alike; for everyone who finds the Christmas tale a source of timeless beauty and wonder; a compassionate, emotional novel of divine love.

New from Marjorie Homes is the dramatic and deeply sequel to this timeless novel. It is called Three From Galilee: The Young Man From Nazareth, the wonderful novel that explores Jesus’ “lost years” between the ages of twelve and thirty. A vivid and unforgettable story.

Of all the books I have written, Two From Galilee will always be dearest to my heart.

It goes back, no doubt, to that magical Christmas Eve in a candlelit church when I sat next to my thirteen-year-old daughter, so close to the manger scene we could smell the hay. Real hay…its pungent fragrance transporting me back to the sweet-smelling fields and barns of my Iowa childhood. Filling me with a sudden, almost overwhelming sense of reality. For the first time in my life I realized, “Why, this really happened! On this night, a long time ago, there actually was a girl having a baby far from home…in a manger, on the hay!”

A very young girl surely, for I remembered reading somewhere that in the culture of Mary’s time every girl was considered ready for betrothal and marriage as soon as she went into her womanhood. And I thought, astonished: “When Mary bore the Christ child, she couldn’t have been much older than my own Melanie here beside me!”

With this sudden awareness came a thrilling conviction about Joseph: He must have been a young man, too. Old enough to protect and care for Mary, but young enough to be in love with her. And she with him. Why not? They were engaged to be married. Surely God, who loved us enough to send his precious son into the world, would want that son to be raised in a home where there was love—genuine human love between his earthly parents. (pp. v-vi, introduction)

And now she was a woman.

She was a woman like other women and her step was light as she hurried through the bright new morning toward the well. She knew she need not tell the others, they would know the minute they saw her. They would read her secret in her proudly shining eyes. And she read knew she need not tell her beloved (if indeed he was still her beloved) though to speak of it would have been unthinkable anyway. He too would know. If, pray heaven, there were some way to see him before this day was past.

She must arrange it somehow...would arrange it somehow. Anxiety mingled briefly with her joy, yet her resolve was firm. Her parents would be shocked if they suspected—she was a little shocked herself. But somehow, some way, before this day was over she would see Joseph. Make him realize that at last she too was eligible to be betrothed. To be married.

For she was a woman now.

In the doorway, Hannah pulled back the heavy drapery which smelled musty from the long rains, and watched her daughter go. Her eyes yearned after the small lithe figure in the blowing cloak, balancing the jug upon her head almost gaily, despite the dragging pain that even Mary could not deny. “Let Salome go in your place,” Hannah had offered, to spare her. But Mary had been insistent. “Of course not, she’s younger. It’s Yahveh’s way with women, that’s all. And all the more reason I should carry the water. I’m a woman now!”

“How long can I keep her?’ Hannah grieved, watching her first-born daughter disappear at the bottom of the windy hill. “How long will it be? Surely the Lord gave me the comeliest girl in Nazareth.” She turned back into the house with a proud if baffled sigh. “Never did boys regard me with such longing as boys have regarded Mary from the time she first ran playing in the streets. Never did my own mother look thus upon me.”

Mary was well past thirteen. Fortunately, her coming had been late. Something clanged harshly in Hannah. She herself had been barely twelve when given to the vigorous Joachim in marriage...But no, she would not dwell on that. He had proved a wonderful husband in the end, and if possible he loved this exquisite daughter even more than she did. He would not be pressured into a betrothal even now; he would save Mary for the proper suitor. Sentimentalist though he was beneath that gruff exterior, Joachim would never yield to foolish pleas. When they gave over their Mary, it must be to someone both rich and wise, someone truly worthy of so exceptional a bride.

The sun was fully up now, its pink light softening the objects in the rude, small room—the low table with its benches piled with cushions, the chest, the cold unkindled oven. She had better rouse the other children. But Hannah refrained a moment, savoring the thought of them sprawled on their pallets. Mine, she thought, and shuddered at the never-ending wonder. Yes, even though her eldest son was crippled and would never see the light of day...even so...out of these loins that were cold and empty so long, suckled at these breasts...

And she pondered Mary’s words—“the way of Jahveh with women.” So bravely spoken, and so vulnerable, somehow. Hannah’s breasts ached even as she gave a cryptic little laugh. She began to call the children, crisply, that they might not suspect her emotions, and cracked a stick of kindling smartly across her bony knees. The hurt of being a woman—she would draw it into her own body if she could, she would spare her child the whole monstrous business.

But no, not monstrous, she sternly corrected. Simply the Lord’s reminder that women were less than men. An afterthought, a rib. And it struck her as wry and startling that he should deign to honor one of them by making her an instrument of his great plan. For it was to be out of a woman that the Messiah would come. A virgin, a young woman. Not carved out of noble new-made clay like Adam, ready to smite the accursed Romans and bring Israel to her promised glory. Not flung like a thunderbolt from an almighty hand. No—as a squalling baby, the prophets said.

Out of one of these selfsame humble, unworthy, bleeding bodies. And thus it was that every Jewish woman cherished her body for all its faults and thought: Even I could be the one. Thus it was that mothers looked upon their daughters as their breasts ripened and thought—even she! But not really. There lay in Hannah a practical streak as salty, flat and final as the Dead Sea. She was not one to pray overlong or fast and hear the fancied sounds of harps and angelic wings. She was not like her sister Elizabeth whose husband was a priest at the Temple and who consorted with the holy women there. She had Joachim and her five children and for her that was enough. When the time came (and it was near, many thought—after five hundred years of exile and slavery!) it would come, that’s all, and have little enough to do with her. (p. 1-3, Chapter 1)

The pink light was claiming the sky. The very breath of God was tinted as mists drifted down from the hills, across the fields, blurring groves and vineyards. Foliage sparkled with last night’s storm and petals gemmed the streets. In all the little houses people were stirring, and the singing that always signaled the beginning of a good day in Nazareth joined that of the birds. There was the smell of bread baking. And passing the big public oven dug near the well for the use of the poor, Mary could feel the heat of the coals and the crone Mehitabel slapped her loaves upon them.

“Mary!” Other girls carrying jugs or skins or leading livestock to drink at the trough, cried out to her. And it was as she had expected. Her cousin Deborah, who missed nothing, pounced on her secret and made it news. Above the creak of rope and bucket, the slosh of water being poured into pitchers and jars, the mooing and blatting of sheep and cattle, the ripple of it ran through the crowd. “Mary’s a woman now!” Offering a mixture of congratulations and commiseration, they made room for her nearer the head of the line. Old Mehitabel joined them, her cackle splitting the bright fruit of the morning. “I say it’s just the beginning of a woman’s misery. A heavy price to pay, I say, because Eve ate an apple. Now if it had been a pomegranate or a melon!...”

The women laughed. They could see a joke. For wasn’t their entire existence based on a proud if almost ludicrous anomaly? Here were the Jews, God’s chosen people—yet none had known such bitter hardships. And their land for generations had been occupied by heathens to whom they must pay tribute, but whom they would not deign to touch. There was something crudely cleansing about Mehitabel’s audacity.

Another voice spoke up. “But nobody’s really a woman until she’s lost her maidenhood. When that happens let us know, that’s when we’ll celebrate!”

Mary flushed. You must be thick-skinned to be a Galilean woman. You must not mind these jokes. Modesty quarreled with this brash discussion of the state they seemed to value above all else. The coming to bed with a man, the loving and begetting. But how could she blame them when her own thoughts could dwell on little else? Cleophas, Abner, the others, but above all, Joseph. Adored as a child, dreamed of as she grew older, scarcely daring to hope. One day she had summoned the courage to ask him, “Why haven’t you ever been betrothed?”

“Can’t you guess?” he smiled. “I’m waiting for you, little Mary.”

After that it was their secret, almost too precious to discuss. Yet a baffling change had come over him these past months; he avoided her, she never heard his voice except in the synagogue. Why, why? Had she done something to offend him? Or was he bowing to Hannah’s snubbing, too proud to beg for what he could not win? Heartsick at the prospect, Mary swung the bucket over the worn stone lip of the well and drew it up. Or had he changed his mind? The prospect was staggering. Could it be that Joseph had found somebody else?

Hoisting the moist weight of her jug to her head, she fell into step with Deborah, who had shooed her little sister ahead so they could talk as they climbed the hill. The child was plainly disgruntled, and although Mary felt sorry for her she was grateful. She was anxious to question Deborah, whose high white forehead and long elegant nose seemed almost to sprout antennae, so alert was she to all the latest gossip. Deborah would have heard. (pp. 12-14, Chapter 2)

Joseph could bear it no longer. Blindly, scarcely knowing what he was doing, he had flung off his leather apron and run out into the streets...Abner. The thought of that cold thin-necked creature ever laying his skeletal hands on Mary filled Joseph with such revulsion that he almost wretched. As for Cleophas. He caught up a rock and hurled it savagely over a precipice.

The handsome face taunted him. The heavy-lidded eyes, the seductive, gaily jeering mouth. Again Joseph heard the remark that Cleophas had made about Mary one Sabbath on the way to the synagogue. It had set Joseph at his throat. One minute friends, the next murderous enemies, they had rolled in the dust, dressed though they were in their best garments, battering each other. Then, panting, both were on their feet, and Cleophas, with an expression more of surprise than anger, was staring at the blood from his splendid purpling nose.

“Just look what you’ve done to my robe,” he’d scolded, grinning. “Now I’ll have to go home and change.” He glanced about, alert for his reputation. “Fortunately nobody saw us. And for her sake I won’t speak of this if you won’t.”

“For her sake!” Joseph had cried, furious. “What of that vile thing you said about her?”

“Oh, that. Come now, don’t tell me you haven’t thought of her that way yourself?” Suave even in his dishevelment, he had mopped his face with the skirt of his striped linen robe. “Or is it milk that flows in your veins instead of good red blood?” Cleophas laughed richly, flinging out his hands—“Of which I seem to have no lack!”

“What you lack is a decent tongue.”

“True, true,” Cleophas admitted cheerfully. “My tongue has been colored, no doubt, by the talk I hear in the ports of Tyre and Sidon. But I assure you I meant no offense either to you or to our pure and beautiful Mary.” He had even slapped a jaunty hand on Joseph’s taut shoulder. “And now let’s go before the gossips come along and ruin all of us.”

His rival’s casualness only increased Joseph’s indignation. From that day the mere thought of the merchant’s son had been enough to make his fists clench. And now it was he, even he, his mother said, who was about to seek Mary’s hand. (pp. 32-33, Chapter 3)

Upstairs, Deborah was helping Mary unbind her hair. She yanked the pins from the dark coronet and impishly began to tumble it about. “Come, come,” Mary protested, laughing. “Hand me the comb. It’s a maid my loosened hair is supposed to symbolize, not a wanton.”

Deborah held the comb wickedly away. Her slant green eyes were dancing. “What a glorious joke that would be, to sit demurely on the bench with disheveled hair all day, knowing that you were no virgin as the visitors believed, but wild and wanton.”

“It would be dreadful I should think.”

“I thought of it at the time of my own hair’s unwinding. I didn’t feel demure and virginal at all, but wanton. I thought how it would be if I had lain with some of the boys I’d kissed, and almost wished I had!”

Mary smiled at her cousin’s self-dramatics. “But what about Aaron? Don’t you love him?”

“Plenty of time for Aaron when he leads me to the marriage bed.” She attacked with the comb so vigorously that Mary winced. “As for love, you tell me what it’s like. How does it feel when you look at Joseph, what is it like when you kiss?”

“We don’t kiss,” Mary said softly. “Not yet.”

“You will. You’ll find they’re all alike, they can hardly wait. Even Aaron—this betrothal has been one long struggle. Don’t you tell,” she whispered. “It’s legal, of course, but still a disgrace. I wouldn’t think of it. But then, I’m not tempted.” She shuddered. “His lips—they’re like kissing a sausage.”

Mary gasped, shocked if amused. A sausage was heathen food. “Oh, Deborah, no, it shouldn’t be like that! When Joseph looks at me it’s like drowning sometimes, almost too lovely to bear. And his touch, even his hand on mine! I dare not even imagine what the rest of it will be like.”

“Well, you’re lucky.” Deborah took up the wreath of blue forget-me-nots. She could hear the other girls coming with their garlands and she wanted to be first. She felt very possessive of Mary; she wanted to claim and crown her, this cousin whose beauty had always been a thorn in her side, who seemed born to be loved. “But you’d better be well chaperoned, you’ve got a long wait ahead.”

Mary too could hear the patter of her friends’ feet approaching. Her hair spilled over her shoulders in a sweet cascade, the shining hair of her maidenhood. A thrill of longing pierced her as she thought of the impending hours, months of waiting. Yet surely there was reason in postponement; surely it would only enhance the time when they could truly be together.

She smiled at her restless, importunate cousin. “The Lord will give us both strength,” she said. (pp. 61-62, Chapter 5)

She had never been so happy, so poised upon the brink of wonder. She felt a tender ecstasy in every living thing: her parents, the hobbling grace of Esau, the very beggars on the street. The little silver-gray donkey in its stall, the blunt-nosed sheep. And the inanimate—the fecund, seedy smell of newly awakened earth—how could she bear its fragrance? The odor of bread fresh from the oven, the raw tangy scent of clay drying on her hands.

She would lift them sometimes as gaze upon them in amazement. To be alive was a miracle, a holy thing. To be alive and roused to your being as a woman. At time she could not sleep. She would rise up from her couch and go out to the places where Joseph had kissed her, under the silvery olive trees. Or she would climb to the roof and lie gazing at the infinity of stars. And the words of the psalm would rejoice in her.

When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars which thou hast ordained;

What is man, that thou art mindful of him? and the son of man, that thou visitest him?

The singing silence of God was overpowering. He would speak to her any moment now. He had a message to give her before her marriage. A blessing perhaps, or an admonition surely; for to marry would be to leave childhood behind. The innocent bliss of its unquestioning acceptance. She had an instinctive knowledge that once she became totally a woman, a wife, she would feel God’s presence so completely no more...

Yes, Lord?...Lord?... It was too late even now; the pure channel of childhood was closed.

Then one day toward sundown she had gone down the path a little way, into the stable cave to water the [donkey]. She had emptied the skins into the trough and the stubby creature had bent its head to drink, when its pointed ears laid back. It shied and made an odd whimpering sound. “Hush now, what’s wrong?” Mary stroked its quivering nose to gentle it, following its blank stare toward the doorway where a shaft of sunlight poured through.

Mary.

She heard her name, and at its sound the little beast reared.

“Yes, Father?” she said, thought it seemed strange that he should be home from the fields this early. “Here I am. In the stall.”

Mary!

Suddenly she realized that it was not her father’s voice that called. She could not place it, nor the source of it, though she went to the low leaning doorway and peered out. The yard and the grove and the adjoining fields lay quivering with the falling light, peaceful and undisturbed. There was no one by the old stone cistern, no one by the vine-covered fence. Strange.

Puzzled, she turned back to the donkey. It had bent its ******* nose again to the water, but only hovered there, not drinking. Its sides were heaving. She could hear its uneasy breath. And now her own heart began to pound. She clutched its dry fur for comfort. “We must be hearing things, you and I,” she said.

Then she saw that the shaft of light pouring dustily through the doorway had intensified. It had become a bolt, a shimmering column, and in it she dimly perceived a presence. Neither man nor angel, rather a form, a shape, a quality of such beauty that she was shaken and backed instinctively away, though her eyes could not leave that living light.

Mary. Little Mary... The voice came again, gently, musically. Have I frightened you? I’m sorry. Be still now, at ease, there is nothing to fear. I am sent from God, who has always loved you, don’t you remember? He has watched you grow from childhood into womanhood, and now he has a message of great importance. So listen carefully, my child, and heed.

“I am his unworthy servant,” Mary whispered, though she scarcely believed her own voice. She was trembling. Could it be that her recently heightened awareness had affected her senses? Why was she speaking thus, alone with only the beast in the sun-white stall? “What…” it was difficult to form the words, “what is it that the Lord would have of me?”

There was a second of silence. Then, in clear ringing tones the answer came: Behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son and you shall call his name Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High...

“The Messiah!” Mary gasped. Involuntarily, she shrank away. “I? I am to bear the Messiah?”

Even so. And the Lord God will give to him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end.

“But I am unworthy!” Mary cried. She was grasping the nibbled manger; she felt her bare feet upon the gritty earthen floor. The sweat poured down her face. “I have many faults. I have rebelled against my parents. I often envy my cousin. I have impure thoughts. How can I be the mother of this long awaited child?”

God knows the secrets of his handmaiden’s heart. He does not expect perfection. This child that he will send you will be human as well as holy. The Lord God wills it so, in order that man, who is human, can find his way back to God.

“But I am not yet married,” Mary protested. “How can this thing be when it is many months yet before I come to the bed of my husband?”

With God all things are possible, the voice said. Already he has quickened the womb of your aged aunt Elizabeth, so that soon she too will bear a son. Now the Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; and the child that is born unto you will be the Son of God.

“I will strive to be worthy,” Mary whispered. It was a moment before she could go on. For one stark, appalling instant she could feel something fleeing from her, something precious. She felt a sense of incalculable loss. “Behold, I am the willing handmaiden of the Lord.”

She closed her eyes, still gripping the donkey’s fur, the stall. When she opened them again the little beast was quietly drinking, and though the shaft of light still slanted through the doorway its intensity was diminished, the voice of her destiny gone.

But something else remained—some quiet consciousness that told her she must be still and wait now upon God. If he had sent his messenger at this quiet hour of evening, then surely he must be near, perhaps gazing at her even now. Soothing her, calming her, bidding her be still and yield to this astounding command. Again, for the flick of an instant, she felt the whiplash of dismay. Not fear, but sheer human bewilderment.

Joseph! What of Joseph, my beloved?

There was no answer. Only the breathless quiet, heightened by the beast that had dipped its head now contentedly to drink from the trough. The stillness, laced with birdsong. The trembling, pervading stillness that comes with sunset after a hard day’s work, when the body aches with weariness and yet is alive, alert, the more receptive to love. Mary stood waiting, humbled, bowed, flowing out to it, whatever it was. As the glory of God had possessed her in childhood, so it would possess her now in whatever manner it saw fit. Hers not to question, hers not to fear, hers only to submit.

And even as she waited, it happened as the angel had said. The Holy Spirit came upon her, invaded her body, and her bowels stirred and her loins melted, her heart was uplifted, her whole being became one with it—the infinite, the unknowable, the total fusion that is the bliss of God. Beside it even the kiss of Joseph was as nothing, even the dream of becoming his wife.

“My God, my God!” she cried, and the sweat ran down her limbs.

And so it was that Mary knew God and was one with God and became at once his child, his mate and his mother, and the miracle was achieved. (pp. 77-81, Chapter 7)

It had happened.

She had not dreamed it. Nor was it but one last sweet conversation with the Most High before she shed forever the innocence and trust of her maidenhood. It was a thing apart. And if it had been impossible ever to convince Hannah that such things were not untruths to be punished, or at best feverish imaginings, how then would it be possible to convey to her this astounding thing?

Yet it had happened. The finger of God had touched her, the presence of God had consumed her and kindled life within her. As surely as if Joseph had taken her unto himself...

Joseph...she scarcely dared think of him. He had become one of a company of strangers. Her parents, her family, people on the street—all laughed and spoke and prayed and toiled and moved in the usual way, so commonplace as to be well nigh terrifying. They did not know, they did not suspect, they could not see the awful veil that hung between them. They did not recognize the mark of God upon her.

But the time was fast approaching that they must.

She was newly nubile. Her blood should flow freely every four weeks—this much she knew. Yet twice now the moon had waxed and waned. Her breasts were swelling, and the nipples stung like little apples bitten and browned by the frost. Sometimes she felt so dizzy it was all she could do to creep to the chest for her clothes. And the smell of certain foods was nauseating. Once, straining the curds with Salome, her face went as white as the soured milk and she had to rush for the basin.

“What’s the matter, Sister?” Salome asked. “Are you nervous about the wedding?”

“Yes, that must be it.” Mary wiped her clammy brown with her apron. “It’s nothing. Please don’t tell Mother.”

Again she had gone into the cave to fill the lamps. And suddenly she could not bear the rich rank smell of the slippery oil. Her hands shook, she dropped and broke a little pink lamp that Hannah had carried all the way from Bethlehem, one that she always kept burning in her room at night.

In a panic Mary knelt to scoop up the fragments, knowing already it could never be mended. Even as she was trying to think what to say, she heard her mother’s brisk step. “Oh, Mother, forgive me,” she pleaded. “I’ll make you another. Though I know how much it meant to you, that it can never be replaced. The last thing I want is to grieve you.”

She could hear her own foolish lamentings while Hannah only stood shaking her head. But her mother’s eyes in the dim half-light of the cave were sharp upon her. “Rise, child,” she said. “You shouldn’t be kneeling on the cold floor like that, it’s nearly the time of your outflowing.” Hannah squatted to pick up the last shreds of the lamp, tucked them, these pitiable precious bits of clay of Bethlehem, into her handkerchief. “It’s not good for a woman to take a chill, it can hold her back.”

So she was watching, Mary realized. Counting the days. And in her dread already providing excuses to stave off suspicion, forestall a possibility too monstrous to credit. Yet the time was fast approaching when Hannah could be put off no longer. Spiritual though the child in her womb might be, God had seen fit to grip her flesh and give it substance. Purely human symptoms that would soon be evident to all eyes. Her parents. Joseph. His people.

What then? What then?

She was confused and frightened. She did not understand. She could only pray blindly: “Help me, help to be worthy of this thing that you have done unto me, oh my God. And these others who are so dear to me—when the time comes that they must know, help them to understand. Don’t let them cast me out!”

Meanwhile, Joseph continued to come to the rooftop, a fervent young shadow still preparing for their wedding day—by which time she would be deep in shame. (Or glory? Oh, God, sustain me, give me courage, let me not drag around drawing puzzled attention in my ignorance and wretchedness; let me grasp thy purpose, let me lift up my head and be proud!) Meanwhile her mother continued to guard her daughter even more zealously against the temptations of youth. And to watch. To watch. (pp. 82-84, Chapter

In the fields and orchards the grains and fruits ripened and swelled, like the bodies of the two women, Mary’s now, as well. And remembering her earlier misgivings, she was ashamed. Why could she not have been like her aunt, swept utterly into the marvel, beyond questioning or human concerns? Then one night she learned that despite Elizabeth’s continual rejoicing, she too had misgivings.

“I feel sure it will be a son,” she said as she walked about in the garden, to relieve her discomfort, after Zechariah was in bed. “I doubt if such a miracle would have been vouchsafed me if it were not to be a man-child.”

“It will be a son,” Mary said.

“Yes, a son, who will be a man of destiny.” Elizabeth caught her breath, stood silent a moment, pulling some dry leaves from the ivy. “With all the penalties that implies.”

“Penalties? What do you mean?”

“It’s a serious thing to be a leader sent from God. It’s a grave thing even to be a priest. There are responsibilities, such terrible responsibilities. And if this be true of priests, how much more so to be a prophet or a king. The mother of such a man pays dearly for the honor.”

Mary couldn’t answer. The Zealots...she remembered. Yes, hideous things happened to them. And often the foaming prophets. They were not men to be envied. But that the king should suffer? The very king?

Seeing how white and still she was, Elizabeth turned and came to embrace her. “Forgive me, Mary, for going on about myself. Or for causing you to worry.” She lifted the small set chin, gazed into the troubled eyes. “My son—greatly as I love him already,” she said, “I know that he will be as nothing compared to the child you are going to give the world. And we must trust in the Lord who will bring this about. We have no right to be afraid.”

“But what will he be like, this child that I carry?” Mary begged. “This baby I have been told is to be the Messiah? The Messiah—I’ve heard of his coming all my life, at home, and in the synagogue, but I’m confused. Will he come as a king to reign over Israel only or over all the world? Tell me, my aunt, you are married to a priest and you have studied. Will he have to go out and do battle with our enemies to bring that kingdom about? And is he going to bring an end to Israel’s suffering as a nation, or an end simply to suffering? All suffering. To the lepers and the beggars and the slaves, suffering such I’ve seen on this very journey, in Jerusalem. And in Nazareth—suffering such as my brother’s blindness.”

“We don’t know,” Elizabeth said. “God reveals to us only as much as we’re able to accept. We don’t know, Mary. And the prophets themselves didn’t know. They disagreed in so many ways. Some said the redeemer will be a king descending in triumph even as you describe; some say he will be a very poor man riding on a [donkey].” Her eyes were shining now, her long lips parted so that her white teeth flashed. “Only on one thing they all agreed—he’s coming, he’s truly coming! And there will be another before him who will help to pave the way.

“And the time is upon us,” she went no. “That much we do know, Mary. And we’re a part of it, you and I. Exactly what our roles are to be isn’t clear as yet. We can only wait and see. But that’s part of the wonder of it, too, the mystery. To wait patiently, not knowing, only trusting—and to try to be worthy of whatever is to be. To know, to have a conviction deep in the heart,” she cried softly, “and yet really not know at all. That’s life, Mary, and it’s also religion. God—who can really know God even after revelation? She asked. “And who can convey to another the essence of the revelation he has had? He can’t, he can’t. We can only wait and find out his meaning, each of us for himself, slowly, gradually.”

Mary was staring at her as if transfixed. And Joseph? She was thinking, What of my beloved? What is to be his role in all this? A sweet anticipation smote her, almost too intense to endure. The Feast of the First Fruits was almost upon them. Already pilgrims were on the road. Perhaps even now he was heading for Jerusalem! (pp. 128-30, Chapter 11)

Hannah shivered, bathing in the brackish water that had grown cold with waiting, then fumbling about for her clothes. How drab and poor they would appear before the finery of the others. She stood a moment, feeling baffled and defensive, feeling afresh her ignorance of the subtleties of draperies and stoles. It hadn’t mattered before; spare and almost boyish as she was she had spurned such trappings as more suited to the dull matrons of Nazareth. And then there had been Mary, so exquisite an adornment in herself.

Hannah set her teeth. She crept, on impulse, into the adjoining chamber and took up the mirror of polished metal. She saw, in a kind of fascination, her own bony cheeks and haunted eyes. She drove Mary’s forgotten comb through her hair; it was no use, she could not comb beauty into herself, and some of the gray strands clung to the teeth like a desecration. She turned to the case of cosmetics. All girls kept these scented pots of color. Sneering faintly at herself, yet with a trembling sense of performing some rite, Hannah scrubbed roses into her wrinkled skin. Her grotesque she looked, like a gaudy ghost going to some festival of the d_____. Yet she felt that she must sustain herself or her sick and quaking limbs would not carry her forth at all.

There now, she was ready. It was the best she could do, and no one would pay attention to her, anyway. All eyes would be focused on the bride, and the proud family of the bride.

Her husband looked at her with great tenderness and pity when she came down, but said nothing. The children were filled with their own excitement. They had been dashing back and forth all day, carrying flowers, stuffing themselves; now they reported that their aunt’s house was already bursting with guests and the courtyard overflowing. “Hurry, hurry, or we won’t be able to see the bridegroom knock!”

They gave her a spray of myrtle to carry and Hannah clutched it, the scent of it harsh and sweet. She felt herself being half-led, half-shoved along. The street was filled with guests bearing torches that lit up the trees so that they sprang at her like wet yellow mouths, belching sounds of merriment. The cymbals were playing, and the lyres. A crowd of youths surged up, already far gone in wine. Aaron was a popular fellow and they shouted his name in fond jests. Hannah could smell their breath as they made way for her and her family, shouting, “Step aside, these are kinsmen of the bride!” Despite the courtesy, Hannah’s skin crawled, for she heard, or imagined she heard, a backwash of comment followed by laughter. How dared they? She turned, longing to claw them with her bare hands, only they had vanished around a corner.

The house of Cora and Nathan was indeed swarming. Some people had mounted lamps on poles and these dipped about the courtyard like winged birds of fire. There was a tarry smell of smoke from the torches along with the perfumes and spices and oils. Their brother-in-law spied them being jostled and ignored and came expansively toward them, his pert homely face also rosy with wine. He was hearty with happiness, clutching Joachim by the shoulder and steering them inside.

“Cora, wife, come, come, your brother has arrived,” he called. And she left off her assertive last-minute adjustings of her daughter’s veil and greeted them effusively. She could afford to be generous, kissing them and exclaiming over Hannah’s robe which she could see had been hastily donned, it was so wrinkled, and glancing at the two pearls over which she had once quarreled with Joachim, for they had belonged to her mother and it didn’t seem right that they be handed on to a crude little urchin from Judea. Well, but her husband could afford to buy her jewels—they flashed now on her hands and in her wads of ornately piled hair. She exuded forgiveness and glory.

“Come, see Deborah, she’s just down from her chamber. Forgive me for saying so, but did you ever see such a beautiful bride?”

“No,” Hannah muttered, “no, never.” She choked on her own jealous love. The words were not merely the elaborate politeness required. “Our niece is radiant, she’s fairer than the crest of Mount Hermon at sunrise.” And it was true.

Deborah was on a raised bench decked with flowers and glistening palm fronds. She reigned there, cool, bemused, a trifle imperious, half-hidden in the gem-shot lavender veil. Her gown was white with a sash of gold, embroidered with flowers and pearls to match her sandals. Her slant green eyes darted about, afire like the emeralds in her myrtle crown. She was all harsh bright sparks and she was very beautiful, but she also seemed disdainful, anxious only to have the whole thing over with.

Her mother regarded her with a candid objectivity. “But more than that she’s always been such a good girl. And Aaron’s such a fine man. Who knows but what this union might produce the hope of Israel?”

Hannah flinched and turned away. “The hope of Israel,” Hannah echoed, though she felt strangled. It was the polite thing to say at weddings. Cora had meant nothing by it.

“The hope of Israel!” some others standing nearby took up the phrase and lifted their cups to the bride, who gave a vaguely contemptuous little nod and lowered her eyes. Joachim did not join in the toast. His grizzled jaw was working; he set down his cup.

Dressed in white the bridesmaids foamed about the little dais, holding their lamps aloft. They were singing the ancient wedding songs. Salome was among them, enjoying herself. Let her, Hannah thought, and raked such consolation as she could from the child’s slight loveliness. Let Salome at least draw pleasure from these doings. As for herself, she was here, she had been forced to come, let her enjoy herself as well. For life was harsh and the grave was always close, so why not celebrate when you can? Rejoice, drink the soothing wine, and toast the honorable, if rather pudgy, bridegroom when he comes.

Hannah’s rouged cheeks began to flame; she could hear her own voice ringing out, joining the songs that praised the virtues and beauty of the bride, who had never been the equal of her Mary, but who was unsullied, unscathed, and so could sit cool and remote on a flower-decked throne awaiting the arrival of her mate.

“Your hair is like a flock of goats, moving down the slopes of Gilead...Your cheeks are like halves of a pomegranate behind your veil...My dove, my perfect one, is the only one, the darling of her mother!” people chanted. There were tears in Cora’s eyes, Hannah saw with sympathy and a kind of incensed bafflement—for how was it that other women could feel so about their ordinary offspring? And then Hannah’s heart was stirred by the music and the wine and she turned and flung her arms about her sister-in-law.

“Oh, Cora, how fortunate you are!”

She felt Cora go tense in the embrace. A little croak of disbelief escaped her. And turning, Hannah saw a slight commotion in the doorway. The music had stopped, a startled silence washed through the crowd. “Mary!” someone whispered. “It’s Mary and Joseph.”

Oh, no, Hannah thought. But she felt a spurt of defiant gladness as well. For how beautiful Mary was, framed by the doorway in the courtyard, her face shining with the old radiance that had caused people’s heads to turn. And behind her stood Joseph, a trifle diffident, uncertain of their welcome, but never so gravely handsome, as if these past weeks had lent new dimensions to his sensitive face.

No one spoke, the embarrassed crowd drew aside as they entered, Mary bearing her burden high, like a queen. The virgins had stopped singing; exchanging troubled glances, they lowered their lamps. The married women began to murmur, some of them looked uncomfortable. “Such nerve,” someone muttered. “How dare they show up here?”

“Hush, be careful,” a neighbor warned. “That’s Hannah, her mother, standing there.”

“Well, let her hear. If a daughter can’t be trained to keep out of trouble let her at least be trained not to soil a wedding feast when she’s up to her chin with child.”

Hannah had gone limp. Now slowly she was braced to tiger strength. Her fists knotted, her lips drew back. Bridling, she turned and would have rent the speaker limb from limb but she felt the restraining grip of Joachim’s hand. “Stop,” he ordered, beneath his breath. “We cannot spoil our niece’s wedding.”

Our niece’s wedding! That he could think of anyone save his own child at such a moment seemed the final outrage. And she began to keen and wail within, and rock her little one against her breast: Oh, Mary, my baby, my little lost bird, why have you been so foolish as to expose yourself? These idiots, these jackals, they would never believe the truth if it were shouted from the housetops.

Nathan came striding in from the garden. He looked at his wife, who was plainly upset. This was Deborah’s doing. She adored her cousin, no matter what. Evidently she’d bidden Mary to come but said nothing, no warning—oh, she’d always been a sly one. And this marriage to Aaron whom she only tolerated, whom she almost despised—was this Deborah’s way of punishing them for their choice? Oh, what were children coming to anymore?

As for Mary and Joseph, if they had any respect for their relatives or their parents they wouldn’t have come. Yet here they stood, so comely both of them; under any other circumstances they’d have graced the occasion. There was something almost noble about them, making a mockery of their humble state—Joseph a mere carpenter, Mary a woman in disgrace. It would be too cruel to bid them to depart. Deborah would never forgive them. And Mary’s parents had already been through enough, Cora reminded herself with a mixture of acrimony and family loyalty.

Yet something else restrained her. Something she could not explain. An uneasiness smote her, a staggering concern. Hannah’s claim. Hannah’s preposterous hintings, which Cora had squelched, and rightly, as the last-ditch inventions of an overwrought woman well-known for an exaggerated passion for her child.

And yet, the sweet light that flowed almost tangibly from Mary. And Joseph, who stood behind her, one hand lightly cupping her shoulder. The gesture was loving, loyal, that of a heartbroken man who would support his beloved regardless of all the world. And yet more…so much more. Something that baffled and rocked the aunt; that look of secret suffering and gentle commitment on his face. As if something had died within him and something new had been born.

She wanted to cry out with it, to demand an explanation. She wanted, curiously, to prostrate herself before it. She was exalted and repulsed by it and she rejected it with all her being. This was her daughter’s wedding; there was no place for it here.

Deborah had sprung to her feet, hands outstretched. “Joseph! And Mary, my cousin. Oh, I thought you’d never come.” Bending, she threw back her veil almost gaily for Mary’s kiss.

At this the crowd murmured afresh. “These modern girls, have they no shame?” “It’s bad luck, her first child will be stillborn...” But a new commotion diverted them. Word had come from the courtyard. “He’s on his way, the bridegroom’s almost here!”

The news sent people running for doorways and into the garden to see the procession. The maids hastily regrouped, holding aloft their lamps that sputtered in the gusts of air from all the rushing about. The music could be heard drawing nearer, a bright tinkling of flutes and tambours and lutes. People did not resume their singing, they waited in a murmuring suspense, for the knock of the bridegroom on the richly ornamented door.

At last it came—boom, boom, boom! Mighty and demanding, almost comical in its urgency, and yet holy as well—the male for his mate. And people laughed and sang his praises as he entered in his swishing robes of Oriental splendor, grinning rather sheepishly under his fat turban that was so jaunty and gay with flowers. Plump and perspiring he stood before her with shy moist passionate eyes and a dimple in his round chin. He was shorter than Deborah when she stepped down, her face demurely hidden behind her veil.

But he bore her away in triumph and honor, accompanied by the joyful procession of groomsmen and maids. And half of Nazareth trooped after them to the fine house he had built, where the wedding feast was to be held. There would be singing and dancing and toasts most of the night before they would be finally led to the bridal chamber, there to join their bodies in the hope that out of them might come forth a son who would be the saviour of them all. (pp. 163-69, Chapter 14)

Joseph was now very busy in the shop. For a time work had been slack. Many nights long after Mary was asleep he had lain worrying. How would he support her and the child, let alone aid his widowed mother, if people were so offended they no longer patronized him? He tossed and turned or got up to study the Scriptures by the glow of the night light in its niche. He was careful not to wake Mary whose small shadow was thrown against the wall. Mary wrapped in her mystery.

His faith floated in and out of him. He made futile attempts to grasp it where it hovered somewhere in the region of his breast, as if he could somehow clutch it, implant it there forever and be at rest. But always, when or how he could not say, it coasted off. He would find himself dry, empty, drained and resigned, avoiding prayer, either formal prayer or that instinctive calling out upon something stronger than he was—something powerful and reassuring.

Then the farmers began to come in. They wanted their tools readied for the spring. He fancied a kind of sheepish apology in some of them. People forgave easily in Nazareth, or they simply forgot. If he had deviated from the proprieties, well so had many of them. “And how is your wife?” they asked.

“Oh, fine, fine,” he responded as proudly as if the coming child were his own.

It was at such moments that the sweet mists of God blew in. He could relax a little as he went about the challenge of his tasks. It was as it had been when he was building his home. He was fashioning something meaningful once more. He was working for love, whether for love of God or of his wife he could not have said. But he whistled as he worked, and in his being almost more than in his mind, he prayed.

Snug in her house, Mary heard the thunder and the pelting rains. “Listen to it, isn’t it glorious?” she said to Timna, who often came to sew and spin with her.

“Yes.” Timna cocked her white head, her blue eyes reminiscent. “Jacob loved the rain.” She always managed to turn the conversation to him. Forgotten were his imperfections, she had adored him and now he was gone and she dwelled on him.

With Timna, Mary felt in harmony, at peace. She had dreaded what the scandal might do to their relationship, yet if anything, Timna had seemed to love her more. “Oh, my child,” she had cried in her gentle, dignified way, “how glad we all are that you have come home!” As for the baby, her only regret was that Jacob had not lived to enjoy it. “He’d always looked forward to having a grandson to teach his trade.”

His trade? A carpenter’s trade for the son of God? Mary wondered. Yet she dared not speak of it. Timna accepted this child as the son of her son. To inform him, “This is not Joseph’s baby, dear Mother Timna, but the child of the living God,” would be both cruel and shocking. Timna would have been forced to reject it, as Hannah had rejected it. As countless others would, no doubt, reject it. Human passion people could comprehend. But the passion of God for man—no, it was too appalling.

A flame of portent licked through Mary. In the protective gesture she had seen her aunt make, Mary cradled her bulging sides.

The rains finally ceased and the cold came down. Joseph tightened the cracks in their house and went up the hill to make fast the house of his father-in-law as well. Mary wove extra blankets for the baby, and swaddling clothes of the softest camel’s hair.

Her confinement would be upon her in early December. Women watched her with kindness now and plied her with tales. Unlike the weaklings of Egypt they prided themselves on easy births, yet they gloated too in their suffering, for was it not so ordered in the very beginning? Mary must be sure to put a knife under her pillow to cut the pain. Drinking purple aloes mixed with hot wine was good, powdered ivory if you could get it even better. Old Mehitabel, the crone at the well, slipped her a dead scorpion wrapped in a green rag. “Put it in your skirt,” she whispered. “It will drive the devils of pain away.” Mary took it fearfully, yet she could not affront the eagerness to help that sprang from those rheumy eyes.

To help. To ease the birth a little, perhaps to share in its glory. Where did all this passion for birth come from, this lust for coming life?

She stood on the mountainside one day with her basket of faggots and dung for the fire. As far as she could see the fertile hills went rolling, flanks tawny, becoming lavender where they melted into the sky. They gave off a pallid sheen, like the flesh that stretched taut across her own belly, shielding its tumbling life. Their eternal rhythms echoed its curve, the shape of her body that cupped and held the child.

And the sky merged with the hills, resting now after their summer labors, yet already rich once more with their hidden burden of life. All the throbbing, pulsing, germinating seeds. “Be fruitful and multiply!” The ancient command would be fulfilled, for the spring rains and sun would bring them leaping forward, all the flowers and grasses and grains and little furred, winged things that now slept so peacefully. Life sprang out of the earth and out of a woman’s belly and had its little span of time upon that earth, and then shriveled up like the weeds of the field and died. But the earth and the sky flowed on forever.

Were they then the only permanence? The only things fashioned by the hand of God that he loved enough to make eternal? Or was there something more, something that he meant to give the world through his coming child? (pp. 172-75, Chapter 15)

For four days they traveled, through the old towns of Nain, Sunem and Jezreel, then eastward across the boggy plains of Esdraelon until they reached the Jordan; then southward through its valley until they must climb again into the bleak hills of Judea. “I wish we dared go directly through Samaria,” Joseph told her as they plodded along. “It would be so much easier for you, but it would be too great a risk.”

Mary nodded. The enmity between the Samaritans and the Israelites had been growing worse. These eternal hostilities, why must they be? Would the time never come when men and nations could live in peace? Or was that the true significance of the miracle she carried? The Messiah. Perhaps through him these terrible conflicts would be settled; he would bring mankind together in love of their God.

She smiled at Joseph. “I am in your keeping. As long as we’re together, I don’t care how long the journey takes.”

She rode along beside him, uncomplaining, either of the cold dry east wind which lashed grit in their faces and made them cringe in their cloaks, or the fierce contrast of the khamsin, blowing its hot stifling breath from the desert. The skies were clear and cloudless after the drenching fall rains, but the nights were intensely cold. Despite the dirt, the jolting, all the discomfort, Mary smiled a great deal, half in a reverie of the coming child. She smiled faintly even as she dozed—as she was dozing now, on this day which Joseph hoped would be nearly the last one of their journey.

Joseph’s feet were sore, his whole body unutterably weary, but he knew he could not be half so miserable as she. He halted the donkey for a moment gazing upon her where she sat, head forward on her chest, one hand braced to support herself. He stood wondering if there were anything he could do to make her more comfortable. The marvel of her electing to come with him seemed more than he deserved. “Mary?” He wasn’t aware that he had spoken, but she started and gazed at him blankly for an instant. “Mary, have you any idea how beautiful you are?”

She laughed. “Oh, Joseph, dirty and disheveled as I am?”

He laid his cheek against hers. Then he took a handkerchief from his girdle, and, pouring a little water from one of the bags, proceeded to wash her dusty face, if only cool it a little. “Would you like me to lift you down so that you can stretch?”

“Yes, I need to walk about a bit.” He set her down upon the hard hot pavement, and she stood there trying to take in her surroundings. “I must have slept. Where are we?”

“Not far from Jericho. See, there’s the river. By nightfall we should be there. Perhaps beyond. And tomorrow night, if all goes well, we shall sleep in Bethlehem.”

“I hope so.” She had not realized how weak and trembling her legs were until she stood. Her body ached, her back was one fierce cramp, and the child was threshing about so that it was hard to speak. She drew a deep breath, still determinedly smiling. “The sooner we can reach Bethlehem the better it will be.”

“Are you all right, my beloved? Are you well?” he asked anxiously.

“Yes. Yes—it’s only riding so long. Come, I’ll walk beside you.”

“Very well, then I’ll ride,” Joseph laughed.

“Would that you could. Poor Joseph. Would that you had a camel to ride, or a horse like the Romans.”

“Would that you were right, for then I would be rich and able to provide so much better for you and your child.”

“Our child,” she said. “This child that the Lord has vouchsafed into our keeping. Oh, Joseph, just because it is my body that will bear him does not mean that he is any less your child than mine.”

“I didn’t father him,” he said quietly. “Nothing can change that. Don’t think I’m protesting, Mary. It is a thing that is beyond protesting. Yet even you must agree that there’s no way to change that fact.”

“No.” She pressed his hand, trying to think how to comfort him. ‘And it matters to you. You would be less of a man if it did not matter, and I—surely I would love you less. And yet…” She groped for the words to express it. “In many ways he will be more your child than mine.”

“More!”

“Yes, more,” she insisted. “A father is so important in Israel. A son needs his father to teach him the ways of the world, and of God and the Law. Once I have borne and suckled this child my task will be largely finished. But yours, Joseph, yours will be only beginning.”

“He may not need a father’s training. He who will come to us as the very son of God.”

“Perhaps he will need it more.” For a minute there was only the sound of the donkey’s hooves on the stones. They could smell the river, now swollen from the rains, and see the cranes that waded its opaque gray-blue waters. “He—surely the one who is to lead Israel out of her troubles—surely he will have to be very strong and wise. And I...I don’t know much about it, but I feel in my heart that he will come to us innocent and uninformed, a child like any child, needing guidance from us as well as from the one who sends him. Both of us, Joseph, but you especially. And that’s why you were chosen. For you were chosen—your honor is as great as mine.”

She spoke with such conviction that a thrill of hope ran through him. He knew that she was seeing this only as she wished to, because she loved him. He knew that he would never be as significant in the eyes of God as Mary, nor would he have it so. But her words had inspired and consoled him, given him new purpose, added an unanticipated new dimension to his destiny. (pp. 182-24, Chapter 16)

For forty days the rude little stable was their home. And each night the great star stood over its entrance. Joseph had never seen such a star, flaming now purple, now white, now gold. Its light illuminated the countryside. Dazed, he told Mary, “I’m afraid there will be others coming to see the child.”

“Let them come,” she murmured. “Oh, Joseph, isn’t he lovely? Just look at him—see, his eyes are open, he knows us! He’s trying to smile.”

“Foolish—all babies smile like that, they don’t know what they’re doing.”

“Oh, but this one does. Our baby does.”

Their baby...Joseph bent over her where she stood unwinding its swaddling bands. She did this several times a day to change it and exercise its limbs. Timidly at first, but now with confidence, she poured a little oil into her hands and massaged the tiny squirming body, the flailing fists, the curved kicking legs. Then she dusted it with powered myrtle leaves. The scent of it, ineffably new and tender, stirred Joseph deeply. He bent nearer and offered one of his fingers, and the child clung to it in a thrilling intensity of trust. It tugged, striving to direct the finger into its mouth.

Joseph laughed, over the pain of his blind adoration. His child. If not the child of his loins, yet it was still the child of his love. He thought of the ancient taboo, that no man should witness a woman giving birth. Yet God had surely led them to this place where no other woman was. The star outside confirmed it. Had that too been a part of God’s plan—to include him thus?

“My son,” he said, smiling. “No, no you must not eat the finger, my precious son.”

The fire glowed day and night, clucking softly, for Joseph went forth each day and brought back fuel for it. And he brought bread and juice and water, and sweets which they ate, often secretively in the still of the night, like children on a holiday. And with them, the core and flower and focus of their existence, was the baby, new, small, helpless, who yawned and woke and gazed at them again. Or cried, so that they would take turns walking him up and down while the other rested.

There was the snap of the fire, the rustle of the hay, the kick of a hoof in a neighboring stall. The starlight poured through the ***** of window, joining the yellow eye of the fire to throw long shadows. They could hear the voices of people coming and going in the courtyard. Music and laughter and raucous shouting floated down from the inn. Camels brayed, harnesses clanked, there was the thump of baggage. All, all made a kind of music for the strange, lovely, half-waking dream.

And sometimes it was interrupted by the coming of visitors, as Joseph had predicted. For the shepherds had spread the tidings. And some came who were only curious or skeptical, but some came who, like those shepherds, marveled and went away rejoicing. (pp. 203-05, Chapter 1

THREE FROM GALILEE: THE YOUNG MAN FROM NAZARETH

THE MAGNIFICENT SEQUEL TO TWO FROM GALILEE

Copyright © 1985 by Marjorie Holmes

From hardback dust jacket:

From one of the most beloved authors of our day, the long-awaited sequel to Two From Galilee:

Marjorie Holmes is a writer unparalleled in her ability to make religious history come alive on the page, and since the first publication in 1972 of Two From Galilee letters have poured in pleading with Marjorie to continue her beautiful story of Mary and Joseph and the child Jesus.

In this wonderful new novel Marjorie dares to deal with those “lost years” of Jesus’ young manhood—the years the Bible doesn’t even mention. Where did he go, what did he do during those years between the age of 12, when he was last seen debating the elders in the temple, and the age of 30, when he actually began his ministry? Was he like other young men of his time? What were those years like for Mary? Was her son as human as his brothers? Was it possible that he, too, could fall in love?

Using her remarkable talent for vividly recreating characters and background, Marjorie Holmes brings Jesus and his parents, brothers and sisters, and friends to life, as if they were real breathing human beings.

Written with great reverence, as only Marjorie could write about such a subject, Three From Galilee: The Young Man From Nazareth—the first part of a two-part serial—is a dramatic, deeply moving, and unforgettable story.

Back cover of paperback edition:

From Marjorie Holmes, one of the most beloved authors of our times, comes the stunning story you have been asking for, the inspiring sequel to her national bestseller, Two From Galilee…

THREE FROM GALILEE: THE YOUNG MAN FROM NAZARETH

Rooted in her broad knowledge of the Bible and of history, Marjorie’s wonderful new novel explores the “lost years” of Jesus’ young manhood—a period not even mentioned in the Bible. Where did he go and what did he do between the age of twelve, when we last see him debating the elders in the temple, and the age of thirty, when he began his ministry? What were those years like for Mary? Was her son as human as his brothers? Was it possible that he, too, could fall in love? With great reverence, Marjorie Holmes employs her remarkable talent for vividly recreating characters and background to bring Jesus, his parents, brothers, sisters, and friends to sparkling life. Three From Galilee: The Young Man from Nazareth is a dramatic, deeply moving, and unforgettable story.

Hannah had been restless all night. Her husband, Joachim, beside her on the pallet, heard the dry rustling protest of the straw tick repeatedly as she threshed about, felt her small bony hand groping for his. A habit she didn’t know she had, but one that always moved him strangely. She had been so young when he first brought her to his bed—scarcely twelve—and so frightened. But in sleep, at least, so trusting.

As he had clasped that tiny claw long ago and so many times since, he clasped it now, stroking it, trying to soothe her.

“Mary!” she cried out plaintively. “Mary.”

“Hush,” he muttered, though his own heart broke. “It’s all right, Hannah, my little one—the Lord is with them.”

If his wife heard, she gave no sign. With a little jerk, the hand was withdrawn. She turned on her back and began to breathe deeply. Now it was her husband who lay troubled, staring into the darkness.

Where were they? It had been weeks since a messenger from the caravan had brought them Joseph’s letter. Their obvious poverty smote Mary’s father. For it was written, not even on papyrus but on a shard of pottery, this letter saying Mary and Joseph were leaving Egypt at last. “Jerusalem should be safe now. I’ll surely find work there.” Mary and the child were well, Joseph added.

Hannah had wept wildly. “But when are they coming home?" she demanded of Joachim. “When will I ever see my grandchild?”

“Now, now, they will write again,” he told her.

But this silence. This strange silence. Mentally Joachim lay tracing their journey. They would come along the coastal plain, the Derech Hayam, Way of the Sea. He hoped they had joined a caravan. He thought of robbers—and of that devil Herod. For the news of Herod’s death, which had brought such great rejoicing, was only to be followed by a cruel blow: another monster was mounting the throne, Herod’s son, Archelaus. This news evidently hadn’t reached Joseph before they departed.

No, now, stop it. Worries loomed larger in the darkness, multiplied, did no good. Joachim kicked off the coverlet, then turned and trudged back to tuck it about the small figure hunched against the wall. (pp. 3-4, Chapter 1)

Mary sang too as she opened the little bag of locust flour she had brought all the way from Egypt, and mixed it with spices and honey. Her heart, like the doves, had scarcely left off its singing since her return. She felt akin to the doves, and grateful, as if God had sent these little messengers in welcome and reward, to observe the time of her own homecoming—and something more: to celebrate her life in its own new season.

For she realized now that she had been just a girl when she left, a very young girl, scared, confused, torn between her desperate love for Joseph and the awesome responsibility the Lord God himself had seen fit to put upon her body. No, more than her body—her very soul. But she had returned a woman. She had become a woman in that stable, in their ordeals in the desert, in the want they had known in Egypt, in Joseph’s arms. Toughened by suffering, uplifted by love, she had failed neither her God nor her husband.

She could go forth into the morning, head high, fearing nothing, a proud young wife and mother leading her beautiful son. The women at the well confirmed this; they threw their arms around her in welcome, made a place for her in the line. There was the creak of rope and buckets, the sloshing of water into their vessels, a merry chattering above the mooing and blatting of animals at the trough. They vied to be the first to share the village news, the latest gossip. Her own seeming fall from grace no longer mattered, they lavished kisses and compliments on her child.

Even her cousin Deborah, who now had two little girls clinging to her skirts. “Mary, Mary, why are you always so favored?” Deborah wailed. Deborah had a catlike beauty, a lively, excessive quality that made her dear. Their mothers had never quite succeeded in making them rivals. “Isn’t it enough that you snatch the handsomest man in Nazareth from the rest of us? Do you have to produce such a firstborn son?”

Mary hugged her, relishing the old exaggeration: caustic, playful, half envy, half genuine affection. “Nonsense. Your Aaron is a wonderful man, and your daughters couldn’t be more fair.”

Smiling as she remembered, Mary put the cakes onto the coals. They were made from a recipe given her by a Bedouin woman. How kind and hospitable those dusky, jet-eyed people. Several times they had offered shelter in their long, black tents: once from a sandstorm, again on bitter cold nights when jackals howled and there was nowhere else to turn. Mary had winced to see the women and children eagerly pulling off the heads and wings of the locusts, creatures that at home only spelled disaster, then drying the little bodies in the sun to be beaten into flour. But the little locust cakes were delicious.

She would carry some to Salome. Her sister had given birth two days before. Only a daughter, to everyone’s disappointment. Nonetheless, there would be a celebration feast. Oh, there was so much to celebrate, and the doves proclaimed it! She would take Jesus out among the birds again, as she had promised. They would climb the plateau that encircled the town, so she could show him his homeland. They would follow the back route, and on the way they would gather flowers.

The dew was still heavy in the grass; their sandals were quickly soaked. But even this seemed wonderful after the brutal heat of Egypt. Sometimes Mary’s throat still went parched and dry, and she would gulp whole pitchers of precious water. Her skin had lightened somewhat, but its sense of burning remained; she felt burned to the bone, seared by some fierce yet sacred fire, perhaps necessary to her own cleansing and reshaping. That must have been what God willed for her—and for Joseph. But even as the Lord had led their forefathers, he had brought them out of Egypt! They had returned to Nazareth and to Galilee, the very flower of Israel. Their Promised Land. Pray heaven they would never have to leave it again. (pp. 15-17, Chapter 2)

The dog was finally wrapped in a blanket and put in a basket beside Jesus’ bed. Later in the night Mary awoke to hear her son sobbing. Carrying a lamp, she tiptoed around the pallets of the other children. The basket, she saw, was empty. The small battered bundle was cradled in his arms. “He came to me!” Jesus said. His face was radiant even as the tears rolled down his cheeks. “He crawled out of his box and dragged himself to me. He is healed, Mother, I felt it. God is healing him! But he mustn’t go back to the fields,” the boy pleaded, “or the jackals will attack him again. He must live with us.”

Troubled, Mary sat down beside them. Her own fingers crept to the warm little head. “That would be very unusual, my darling. You know Jews don’t keep dogs; only Egyptians keep dogs.”

“Uncle Cleo does.”

‘Well, yes. A few rich people like Cleophas,” Mary laughed. Joseph’s oldest friend Cleophas rode a horse as high-spirited as he was, and beside it paced a hound he had brought from Cairo. But then Cleo had always been a law unto himself: merry, arrogant, thinking his father’s money could buy him anything. At one time, even Mary’s hand, Mary smiled to remember. Poor Cleo—his astonishment had been almost comical when her father gave her to Joseph instead. And Hannah was so distraught she took to her bed; she had been so anxious for Mary to have the merchant’s son…How strange life was, these battles caused by love. Yet now Cleo was like a favorite uncle to her young.

Mary was stroking the puppy cuddled close to Jesus. “But it isn’t the custom for people like us to have a dog.”

Jesus sat upright. “Bad customs should be changed, Mother! Dogs are God’s creatures. Dogs need people and people need dogs. It’s a bad custom not to love and care for dogs.”

Joseph relented, of course; he could deny his family nothing. And with a speed that astonished everyone, the dog healed. They named him Jubal for the joy he brought them. Also for the way he tried to join in when they were all singing and tootling away on the instruments Joseph had fashioned for them: timbrels, a flute, some horns, even a lyre. Esau, Mary’s blind brother, helped him; Esau had an uncanny feeling for musical things. The candles in the shop burned late as the two labored to make the wood like satin, the metal bright, eagerly testing the tender strings. Joseph had never been happier. Almost every night, after prayers and the evening meal, he would gather his family on the rooftop, and there, head cocked, beating time and smiling proudly even as he piped, Joseph would lead them.

Mary, putting the last dish in the cupboard or laying the fire for morning, sometimes felt like dancing to hear them, her darlings, like so many birds on a bough. Wiping her hands, she would scurry up the steps to sit beside Joseph on a cushion, listening with her shining eyes and her heart.

It was cool there under the stars; jasmine spilled its white fragrance over the wall, sweet…sweet as the sounds they were making, so young and bold and yet plaintive in the night. Her whole being seemed in tune with this music of her life. The very stars seemed to tilt toward her, sparkling, blazing, as if they too were striving to speak or sing. How close God seemed! Mary had not heard the voice of her Lord since childhood; not once since that incredible experience in the shed. Not even the voice of an angel, although, strangely, angels had repeatedly spoken to Joseph in dreams. Yet on such nights she felt as if the whole company of heaven were swirling close, blessing her, blessing her. Compressing as much happiness as possible into these few years.

For deep within her, on quite another level, Mary walked a dark and lonely road: aware, ever aware, of the changes sure to come...

Cleophas often dropped in on these evenings, still darkly handsome in his fine striped silks and jewels, bringing presents for the children. His own marriage had been a sad one. His wife was sickly; she had lost three babies before fleeing in disgrace to her parents in Acre. Cleophas had gone after her repeatedly, to no avail. Mary and Joseph welcomed him. They knew he envied their happiness, yet it comforted him to be near them.

“Cleo! Uncle Cleo!” The children pressed their instruments upon him. “Come join our music!” With a vigorous hug for everyone, he would perch on the parapet, and pretending at first to be confused, pluck clumsily at the lyre. “No, no, Uncle Cleo, you are holding it upside down!” the younger ones would shriek. “Ah, like this?” His eyes, under their sleepy lids, twinkled. Suddenly long sleek fingers flew, rings sparkling, his voice rang out, and oh, such merry melodies as now raced toward the stars. The little dog, lying at Jesus’ feet, would lift his head and howl.

“Listen, he’s singing too!” the children chanted.

“That pariah?” Cleophas teased. “That bobtailed wretch? He’s trying to tell us to take him back to the jackals.”

‘No, no, we love him, he’s beautiful!” They beat at Cleo with frantic fondness. “God sent him to us and healed him! His sores are all gone, see his shiny coat! Even his stumpy teeth grew in straight and strong!”

“He’s still limpy,” Cleo persisted, laughing as he fought them off. “He will always have a stubby tail.”

“At least he has a heart.” Joseph grinned. “Not like that cold-blooded hound of yours. Where did you get him, out of a tomb?”

They were always trading insults—Cleophas vehement, often outrageous, Joseph cool, composed, amused. It had been so since boyhood, this mocking affection between them. Joseph had worried about Cleo—his wild ways. Once he had even fought him to the ground over Mary, bloodying his best Sabbath robes. Yet they remained close. Their eyes met now over her head. How small and dainty she still was, after her day’s work. She wore a soft little blue garment, tied at her tiny waist; she had wound a ribbon through her dark hair. A few curly tendrils escaped as she moved about, gently but firmly quieting the children. So young, so small and virginal…for a moment it seemed incredible that she should be their mother.

Jubal was devoted to them all, especially Mary, but Jesus was his idol. The dog slept beside him at night, and followed him to school, where he would flop down on the synagogue steps and wait patiently until the boys came shouting from their studies. Then, with a yip of delight, he would leap to greet his master.

Toward midafternoon, in the courtyard of her house, Mary could hear him barking, a signal that her sons were coming. In a minute Jubal would hurtle through the heavy drapery at the doorway, eyes bright, tail frantically wagging. Mary hugged him and gave him his bite of the goat’s cheese or sweetmeats she had waiting. Meanwhile, her oldest daughter, Ann, helped her pour mugs of milk and portion out the treats.

The children swarmed in, Jesus tallest—nearly as tall as she was now—followed by young Joseph, whom they had taken to calling Josey, and James. Josey was a ruddy, noisy boy, very active and aggressive. He liked to climb, wrestle, throw things, grab things. He was inclined to be belligerent. He was always teasing James, who was more gentle, a shy child who had his aunt Salome’s way of looking up at you with a sudden charm from beneath lowered lids. James was often bewildered and frightened at Josey’s antics, running to Jesus for comfort or protection. How fast they were growing, Mary’s heart protested. Next year Simon would join them; Jude would be at her skirts a few more years. She was grateful for toddlers and daughters. (pp. 51-55, Chapter 3)